Tracing Time: A Book Review

/Book Review

Tracing Time: Seasons of Rock Art on the Colorado Plateau

By Craig Childs

Torrey House Press

Paperback

228 Pages, $18.95

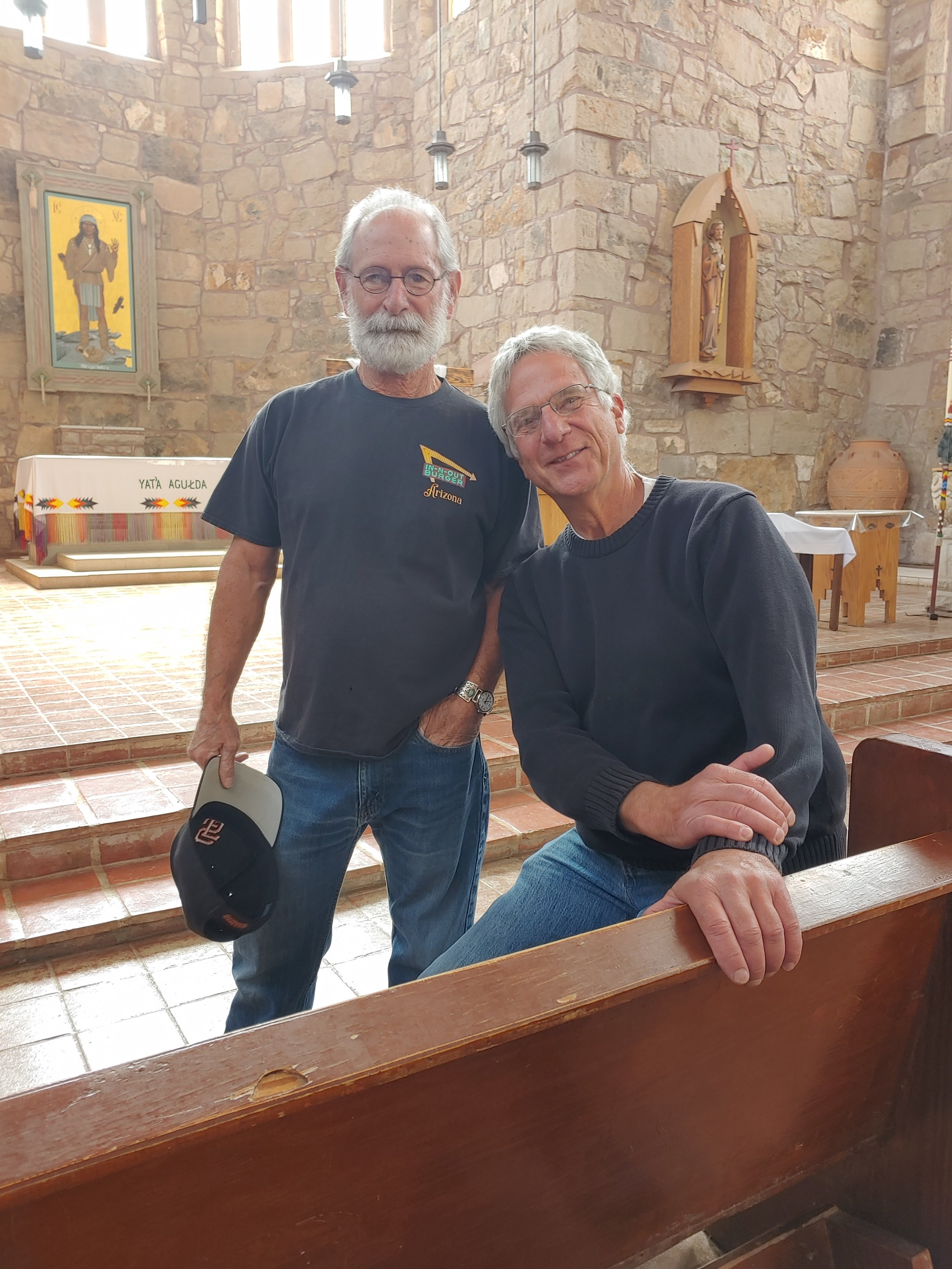

Review by

Pete Warzel

Craig Childs is a naturalist, environmental activist, adventurer, desert rat, and a wild man. Wild because of some of the risks he takes, like swimming in flash floods, maybe riding is a better description, and chasing bears in order to capture photographs. He is also an extremely talented writer.

Torrey House Press is a non-profit publisher based in Salt Lake City, focused on a “literary” approach to environment and landscape particularly in the American west. The firm is now twelve years old and publishes elegant, relevant books. Tracing Time: Seasons of Rock Art on the Colorado Plateau, is a fine, recent example.

Craig Childs and Torrey House are made for each other.

Childs puts the personal in his writing, starting mostly from a hand’s on, first person experience, that leads you into his vast knowledge and research on the subject. He is a master of the southwestern mountains and desert, all that inhabits that land, and has become an expert on the ancient ones who roamed the stark geography for thousands of years. House of Rain: Tracking a Vanished Civilization Across the American Southwest was Childs’ exploration of the roots and migration of the Anazasi. The Animal Dialogues: Uncommon Encounters in the Wild, presented his view of nature through reflective encounters with wild fauna, up close and personal. That book presents an amazing piece of writing in three pages, “Hawk”, that describes a hunt by a hawk for a rabbit, by simply describing the tracks, the sweeping wing traces, the dislodged fur, all in the record left on new snow. You never see the action; you know the action by following the signs.

Tracing Time also begins with the personal: “My sport is seeing.” We could add interpreting as a related pastime. Childs is in the frame of each image discussed, then branches out with conjecture, and discussions with experts, he is not claiming to be an expert, simply an observer. It becomes more personal as it all takes place in the initial days and months of COVID, pointing to an exact moment in modern times that marks the long years back to the ancient. His musings are varied for each symbol, his observations so interesting in the detail. Some examples:

Handprints: ‘These were not the marks of generic lives or of gods in legends, but individuals with names and faces, each a different person, a crowd, a room of applause. Holding up your own hand to compare sizes is involuntary.”

Spirals: “Spirals are the high verb of rock art. They are the trappings of motion, like stepping into a planetarium with stars and planets swiveling around a domed ceiling.”

Galleries (meaning a space filled with hundreds or thousands of images, some overwritten through time): “If a rock is living and thinking, certainly the art painted on it is non-stop chatter.” And, “It is what Carol Patterson calls ‘the presence of meaning.’ You don’t have to know what it is, only that it exists.”

The Hunt: “if you encounter rock art while walking randomly, know that it’s not random. You’ve stepped into a pattern. Suddenly you find you are a pin in a map, an axis around which the land seems to turn.”

There are no photographs in the book, rather quite elegant drawings of images from the rocks by Gary Gackstatter, that front each chapter, representing isolated images of the subject pattern Childs specifically addresses. The effect is spare and simple, giving us an idea of the “art”, but keeping the focus on the narrative.

Craig Childs has written a paean to the symbolic work of the Southwest, and the landscape that is integral to the images left for us to ponder. “I am not offering a guidebook to places, but a guidebook to context, meaning, and ways of seeing.” He may offer speculation, or his own reflections, but he never states that this is the translation, this is what it means. He knows his subject first hand, and is well equipped to write the stories in this fascinating look into the past.